Greece

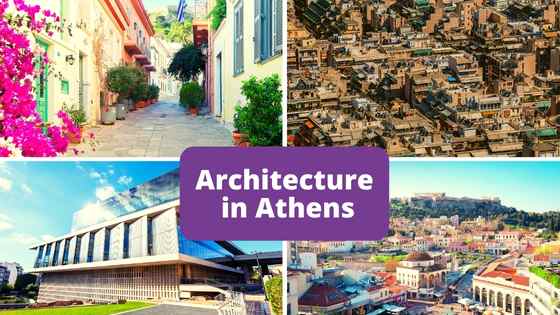

Architecture in Athens

If you like architecture, then you probably know that every country has different laws, different buildings, etc…There are reasons for that, so let’s take a look at “architecture in Athens”.

Athens features a unique blend of different architectural styles. In this rather chaotic but nonetheless fascinating city, one can see an archaeological site, a neoclassical mansion, a tiny quaint church and a modern concrete block of flats within a few blocks.

Following the successful War of Greek Independence in 1821, Athens became the capital of Greece in 1834, marking a new era for this city, and the start of serious construction works, which included buildings, public spaces and roads. Despite its historic past, Athens still looked a bit like… a village. A fair characterisation if we think that at the time it had about 4,000 inhabitants, whereas nowadays it is home to at least 5 million people, approximately half of the Greek population. At that time, Athens lacked the imposing Baroque architecture of its contemporary European capitals, i.e. cities like Rome, but it had also lost the classical grace usually associated with ancient Athens.

First, a bit of Athens history…

Athens was not the first choice as the capital of the newly formed Greek state. The Greek revolutionaries had initially selected the busy port town of Nafplio to be the capital of their new state. However, the European superpowers of the time, such as France and Britain, who had supported the Greek during the Independence War financially, had different plans. Motivated by the idealised image of Athens as the heart of the ancient Greek civilisation, they insisted on making Athens the capital. They had great plans about reviving the classical Greek architecture style, which is why they sent a team of prominent architects there, including the Danish architect Theophil Hansen, Saxon Ernst Ziller and Greek Stamatis Kleanthis.

Neoclassical Architecture

These architects envisioned a revival of the ancient glorious days and had the opportunity to shape the city according to their plans. The result, as photographs from the early 20th century show, is a beautiful city with Neoclassical architecture, wide avenues, grand squares and parks. Its population started to grow quickly and Athens started to look like a European capital.

That’s quite different to the Athens you’ve been to, right?

So, what happened in the 20th century?

The years that followed in the first half of the 20th century left an indelible mark on Greece and changed its route forever, affecting the architecture and urban planning of its capital in their passage.

Firstly, the Greek-Turkish population exchange, an aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, saw 1.5 million Greek refugees leave Turkey and settle in Greece. About a quarter of those ended up in Athens and, as a result, its population grew from 200,000 to 500,000 in a few months.

WWII and the German-Italian Occupation of Greece (1941-45) brought Greek industry, agriculture and infrastructure to its knees. This problem was made worse by the Greek Civil War of 1946-49, which followed and deepened the political, social and economic disparity.

As a result, people were fleeing the countryside and looking for a better life in Athens. During the 1950s, about 560,000 internal migrants poured into Athens, whose population doubled again. There they found the refugees from 1923 who were still living in temporary shelters as well as Athen’s middle class who were living in Neoclassical mansions but did not have enough money to feed themselves, let alone repair their homes after the damages caused by the successive wars.

The Greek concept of antiparochi and the beginning of a new era

At the time, the Greek state had spent most of the financial aid that it received through the Marshall Plan trying to stand on its own feet again after the civil war. As a result, it did not have the infrastructure or the money to provide housing for all these people who were arriving at the capital. This period was characterised by hunger, unemployment, desperation, economic and political inequality; all of which often led to violence. The Greek government needed to find a solution – and fast.

And this is how the system of antiparochi was born, which has no exact translation in English but can be understood as a ‘mutual exchange’. A contractor will approach a homeowner and offer them the following deal: the contractor would knock down their house and build a block of flats in its place – in Greek it’s called polykatoikia, i.e. ‘many homes’. The original homeowner would receive some of flats within the building (usually one, two or three, depending on the size of the building and value) and the contractor could sell the rest for profit. In this way, thousands of people were able to find a new home and a lot of people found employment in construction, helping the Greek economy grow.

It’s worth noting that antiparochi emerged on its own – the people came up with the idea and went into making it a reality. It wasn’t a state initiative and – more or less – unregulated by the Greek state altogether, which also explains why modern Athens looks like it was created quickly, with no central planning.

The urgency of finding a solution to the housing issue in Athens meant that no one was particularly bothered about preserving the Neoclassical architecture of the city, which mostly vanished, giving its place to ugly, grey concrete blocks of flats. In the last twenty years, the state has tried to make up for it by creating stricter laws to save any surviving Neoclassical buildings as well as to regulate antiparochi. Moreover, the city of Athens is trying to regain some of its character through beautiful restorations and pedestrianisation of central spots.

Athens is currently very densely and irregularly built, posing a serious – but also exciting – challenge for the young generation of Greek architects on how they can shape its architectural future moving forward. Modern Athens features buildings designed by famous contemporary international architects as well, such Calatrava, Renzo Piano, Bernard Tschumi, and many more.

At the same time, since many people are more interested in money rather than preserving the beautiful Athenian architecture from last century, the system of antiparochi continues. In areas where there are still some old houses with gardens, people chose to demolish them and build block of flats rather than renovate them. This is because the value of flats and land in Athens continuously goes up, so every owner of an old house, gets much more financial benefit to give it up as “antiparochi”, than do a renovation for an old house with a big garden, which is difficult to maintain in Athens.

Also, contrary to many other European countries, in Greece it is not obliged to build a house or “polukatoikia” with an architect. According to local law, it is enough to employ a civil engineer when building a house. An architect usually makes a house nicer looking, but it also adds up to the bill. Therefore, most buildings in Athens are designed by civil engineers, which means they are safe and practical, but they are not aesthetically pleasing.

Interesting article ! Thanks.

thanks Catherine, happy you liked it. χαιρετίσματα από την Αθήνα